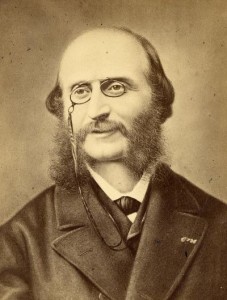

The half-smile with which Jacques Offenbach has been looking at us for the last 150 years from every portrait and photograph reveals more than words can say about the man whose discovery that irony was his sharpest weapon paved the way for success. From his lean face, his sparse, unkempt hair and his intelligent gaze we may imagine the young Jewish cellist who, at the age of 14, left Cologne for Paris, where he arrived penniless but where his striking virtuosity soon attracted astonished attention. The appeal of the theatre must have been irresistible and theatrical life in Paris under Louis-Philippe abounded in novelties that were ceaselessly sought after by an increasingly flourishing bourgeoisie, as demanding as it was affluent. Principal cellist at the Ambigu-Comique and then at the Opéra Comique, Offenbach became musical director of the Comédie Française in 1847 and, finally, in 1855, at the age of 37, he established his own theatre on the Champs-Elysées, Les Bouffes Parisiens.

The half-smile with which Jacques Offenbach has been looking at us for the last 150 years from every portrait and photograph reveals more than words can say about the man whose discovery that irony was his sharpest weapon paved the way for success. From his lean face, his sparse, unkempt hair and his intelligent gaze we may imagine the young Jewish cellist who, at the age of 14, left Cologne for Paris, where he arrived penniless but where his striking virtuosity soon attracted astonished attention. The appeal of the theatre must have been irresistible and theatrical life in Paris under Louis-Philippe abounded in novelties that were ceaselessly sought after by an increasingly flourishing bourgeoisie, as demanding as it was affluent. Principal cellist at the Ambigu-Comique and then at the Opéra Comique, Offenbach became musical director of the Comédie Française in 1847 and, finally, in 1855, at the age of 37, he established his own theatre on the Champs-Elysées, Les Bouffes Parisiens.

In the mean time Paris had seen a small revolution (1848), an attempt to establish a republic (the second) and, in 1851, had become the capital city of an empire (the second, that of Napoleon III). The well-fed bourgeoisie resumed its business activities and became increasingly rich; Paris underwent a transformation and became the monumental city that we now know, pulling down old houses and surrounding itself with vast boulevards. On this bustling construction site, where work never stopped, Offenbach helped his audience to forget how tiresome it was to accumulate wealth and to cultivate interesting relations.

Parisians like to make fun of themselves and Offenbach presents them with a distorting mirror in which nothing that takes place in this capital city is taken seriously. His theatre is inhabited by well-intentioned, corrupt hypocrites, women in search of a sugar daddy, inveterate womanizers, and by policemen who invariably arrive too late. The phenomenal output of his workshop during this period includes the great masterpieces Orphée aux enfers (1858), La belle Hélène (1864), La vie parisienne (1866), La grande-duchesse de Gérolstein (1867), La Périchole (1868), Les Brigands (1869).

Offenbach’s half-smile resembles that of the older Rossini, whom the young Jewish composer greatly admired. These are the same years in which Rossini lived withdrawn in Passy (where he died in 1868), but the ironic expression of the Italian is that with which an old man looks down upon those who engage in restless activity, and the wittiness of his last years is an intellectual game, solitary and slightly melancholy. Offenbach may be his heir, but an heir entangled in the web of present events, from where he keenly observes the pulse of a society in rapid flux, capturing its distortions. His mythological deities, so human in their foibles, remain unforgettable: his couple Orpheus and Eurydice, tired of one another yet compelled by “public opinion” to remain together; his beautiful but evanescent Helen; the Grand Priest Calchas, too busy cheating the Greek kings at their games to deal with serious matters. Tossed in with this is a dizzying play of quotations and allusions, as well as a mingling of language levels (comic, serious, technical, or sentimental) – all of which continually appeal to the complicity of the audience. Furthermore, the link binding this composer to his audience is to no small extent due to Offenbach’s capacity for surrounding himself with librettists (Meilhac, Halévy, Cormon, Cremieux…) and performers (Lise Tautin, Léonce, Désiré, Hortense Schneider, Zoulma Bouffar…) who, gossiped about and eagerly awaited with every new creation, were ultimately perceived by Parisians as the slightly deranged members of an extended family.

Offenbach’s half-smile resembles that of the older Rossini, whom the young Jewish composer greatly admired. These are the same years in which Rossini lived withdrawn in Passy (where he died in 1868), but the ironic expression of the Italian is that with which an old man looks down upon those who engage in restless activity, and the wittiness of his last years is an intellectual game, solitary and slightly melancholy. Offenbach may be his heir, but an heir entangled in the web of present events, from where he keenly observes the pulse of a society in rapid flux, capturing its distortions. His mythological deities, so human in their foibles, remain unforgettable: his couple Orpheus and Eurydice, tired of one another yet compelled by “public opinion” to remain together; his beautiful but evanescent Helen; the Grand Priest Calchas, too busy cheating the Greek kings at their games to deal with serious matters. Tossed in with this is a dizzying play of quotations and allusions, as well as a mingling of language levels (comic, serious, technical, or sentimental) – all of which continually appeal to the complicity of the audience. Furthermore, the link binding this composer to his audience is to no small extent due to Offenbach’s capacity for surrounding himself with librettists (Meilhac, Halévy, Cormon, Cremieux…) and performers (Lise Tautin, Léonce, Désiré, Hortense Schneider, Zoulma Bouffar…) who, gossiped about and eagerly awaited with every new creation, were ultimately perceived by Parisians as the slightly deranged members of an extended family.

In 1870, the devastating Franco-Prussian war signalled the end of the Second Empire, the siege of Paris and the tragedy of the Commune, when both enemies joined forces against the rebellious Parisians. These were hard times for Jacques Offenbach. Both Jewish and German, he barely escaped being accused of connivance with the enemy and with a ruling class that had brought disaster upon France. Offenbach opted for a temporary change of location; he moved his theatre to Milan, to Spain, and to Vienna, the capital of another empire that wasn’t doing too well and that always welcomed him with open arms. If his Paris is no longer in the mood for burlesque comedy, Offenbach reinvents himself in the new Théâtre de la Gaieté, with opéra-bouffe-féerie, even more absurd and fantastic (although there is lively political satire in his 1872 Le Roi Carotte), complete with astonishing effects and a touch of sentimentalism to boot: witnessFantasio (1872), Le voyage dans la Lune (1875), Le docteur Ox (1877) La fille du tambour major (1879), and the Contes d’Hoffmann, which were never completed – a fact that perhaps constitutes its principal attraction since it leaves the work open to multiple interpretations. Paris was soon once more in harmony with Offenbach. The German Jew was to leave as his legacy to French and European music that caustic and complacent irony which still endureswell over a century later.

Having flopped several times and recovered several times (the latter notably in 1876 thanks to a triumphant tour in the United States), it was precisely just after the disasters of the war and the Commune that Jacques presented to the world an image of Paris that was possibly no longer current, but that would remain inseparable from the City of Light that we have all dreamed of, have sought and still seek, and that is still the way Paris likes to think of itself: the city of freedom of speech, of countless opportunities and zest for life, in search of happiness lost.